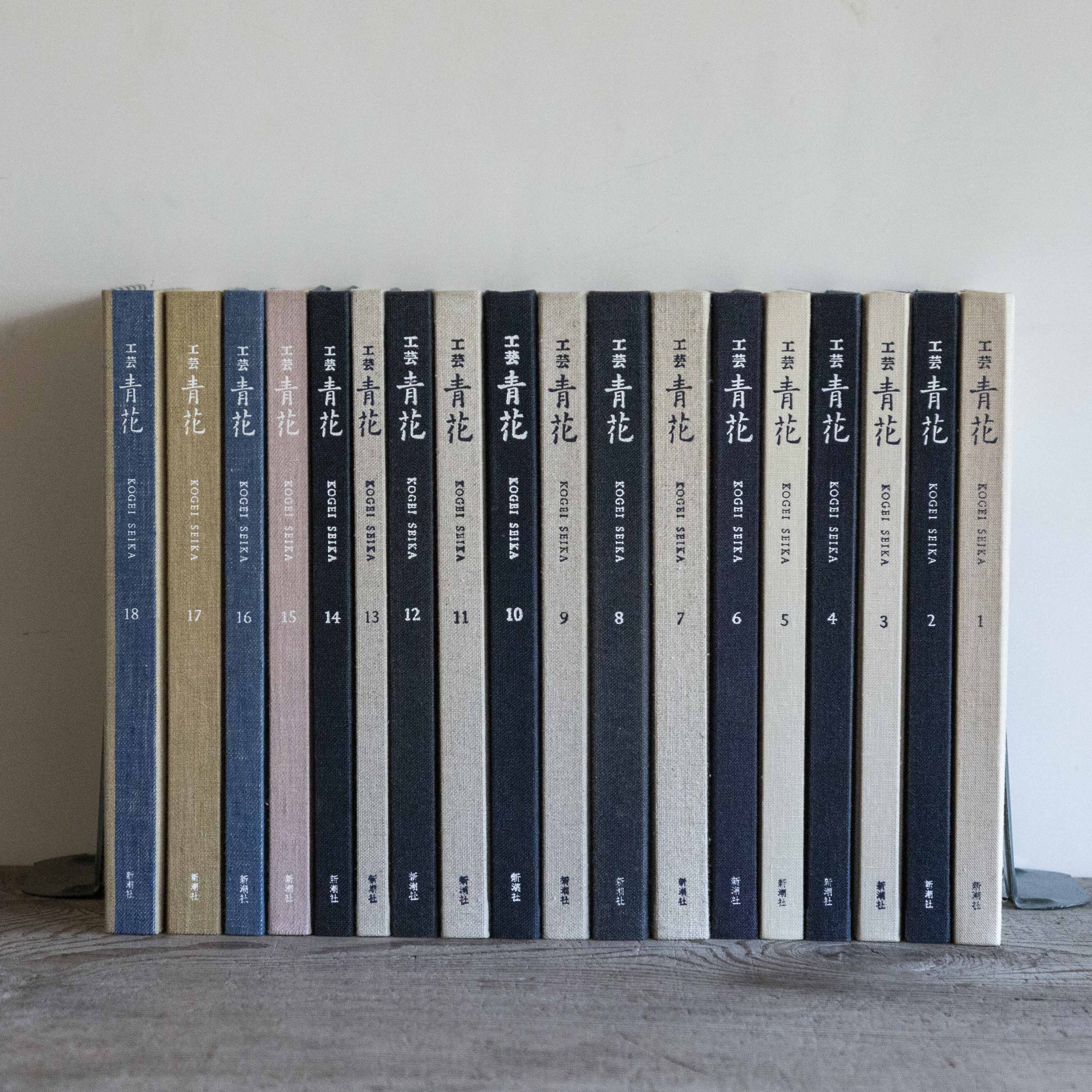

『工芸青花』12号

■2019年8月30日刊

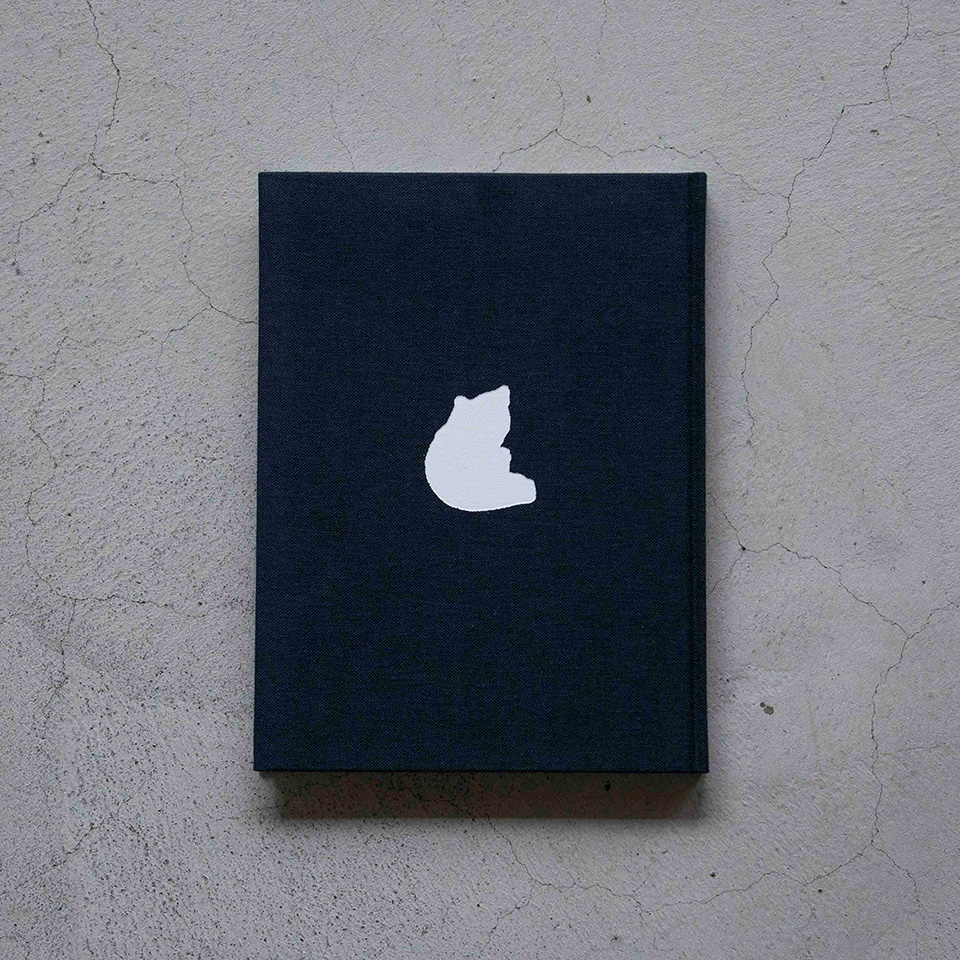

■A4判|麻布張り上製本|見返し和紙(楮紙)

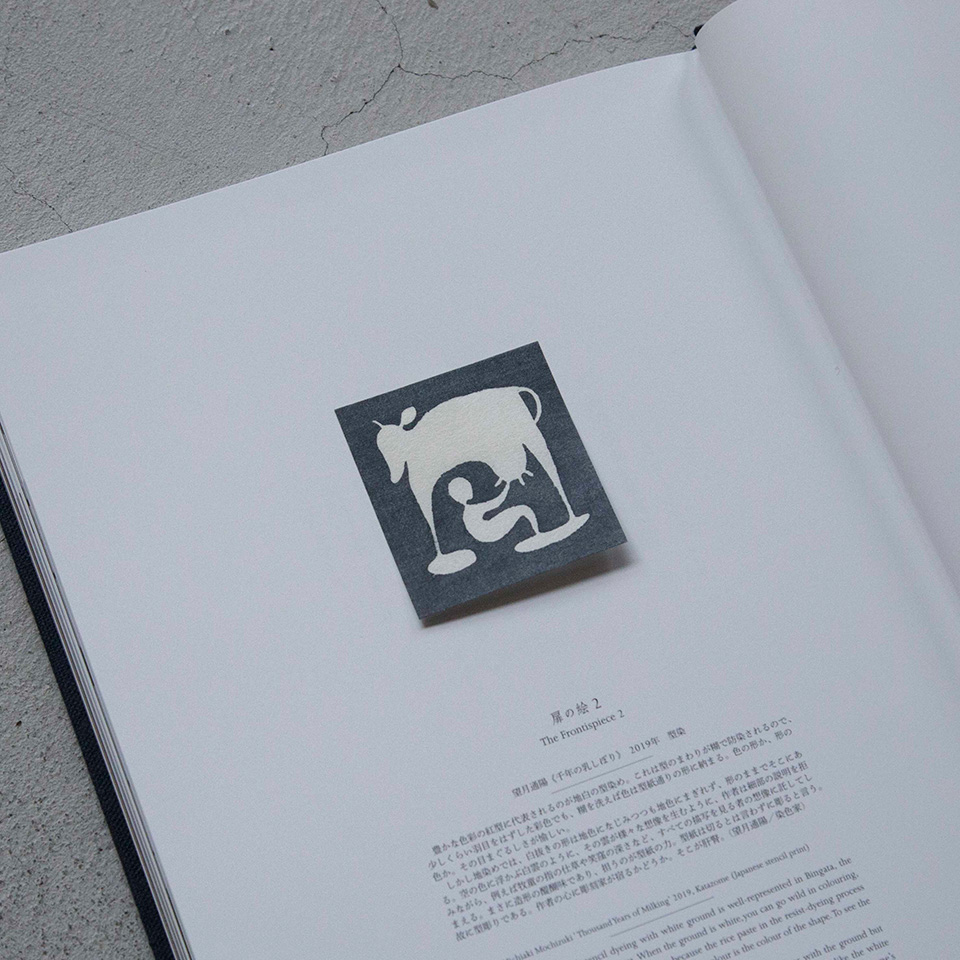

■カラー176頁|望月通陽の型染絵を貼付したページあり

■限定1200部|12,000円+税

■御購入はこちらから

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=289

Kogei Seika vol.12

■Published in 2019 by Shinchosha, Tokyo

■A4 in size, linen cloth coverd book with endpaper made of Japanese paper (kozo)

■176 Colour Plates, Frontispiece with a stencil dyed art work by Michiaki Mochizuki

■Each chapter is accompanied by an English summary

■Limited edition of 1200

■12,000 yen (excluding tax)

■To purchase please click

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=289

扉の絵 2

The Frontispiece 2

望月通陽《千年の乳しぼり》 2019年 型染

豊かな色彩の紅型に代表されるのが地白の型染め。これは型のまわりが糊で防染されるので、少しくらい羽目をはずした彩色でも、糊を洗えば色は型紙通りの形に納まる。色の形か、形の色か。その目まぐるしさが愉しい。

しかし地染めでは、白抜きの形は地色になじみつつも地色にまぎれず、形のままでそこにある。空の色に浮かぶ白雲のように、その雲が様々な想像を生むように、作者は細部の説明を拒みながら、例えば牧童の指の仕草や笑窪の深さなど、すべての描写を見る者の想像に託してしまえる。まさに造形の醍醐味であり、担うのが型紙の力。型紙は切るとは言わずに彫ると言う。故に型彫りである。作者の心に彫刻家が宿るかどうか。そこが肝腎。(望月通陽/染色家)

Michiaki Mochizuki ‘ Thousand Years of Milking’ 2019, Katazome (Japanese stencil print)

The characteristics of stencil dyeing with white ground is well-represented in Bingata, the bright coloured fabric from Okinawa. When the ground is white,you can go wild in colouring, you can get the colour exactly as the pattern because the rice paste in the resist-dyeing process protects the area outside the stencil. The shape of the colour is the colour of the shape. To see the dizzying rapidity of variation in shape and colour is such a fun.

On the other hand, the white shape of ground-dyed fabric harmonizes with the ground but would never dissolve in. By the paste, it is left void in the shape of stencil. It is like the white clouds floating in the blue of the sky, or like the ever-changing clouds that stimulates one’s imagination. The artist can refuse any explanation to the details such as the finger gesture or depth of dimples of a shepherd. He can leave the viewer to imagine every expression. It is a genuine delight of the art and is all by the power of stencil. To make a stencil with paper, you do not say ‘to cut’ but ‘to carve’. Thus, comes the Japanese saying ‘Katabori (pattern carving)’. Does a carver dwells in the heart of a dyer? I think that is crucial. (Michiaki Mochizuki / Artist)

目次 Contents

1 三人とアイヌ

The Three Artists and Ainu

・アイヌ文化概観 閑野譚

・神の魚 前橋重二

2 生活工芸派と二〇一八年

New Standard Crafts Artists in 2018

・日本生活器物展を終えて 三谷龍二

・台北で気づいたこと 菅野康晴

・生活工芸の「ふつう」 菅野康晴

・ふつう、の分かれ道 高木崇雄

・個人的な抵抗 井出幸亮

・器であること 沢山遼

3 村上隆と古道具坂田

Takashi Murakami and the Antique Sakata

・バブルラップ展で伝えたかったこと 村上隆

4 川瀬敏郎と甍堂

Toshiro Kawase at Irakado

・左手の花 青井義夫

5 骨董のさびしさ

Loneliness in Antique

・年をとるとケチになる 青柳恵介

・時々出会う 五十嵐真理子

連載

・ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群 6 堀江敏幸

扉の絵

精華抄

1|三人とアイヌ

The Three Artists and Ainu

札幌にサビタ(ノリウツギの異名。夏に白花が咲く)という工芸ギャラリーがあり、店主の吉田真弓さんと話していて、この特集をつくろうと思いました。吉田さんがひきあわせてくれた三人の仕事を紹介する記事です。共通するテーマがアイヌでした。アイヌ(アイヌ語で「人」の意)とは、北海道、樺太、千島列島、カムチャッカ半島、本州北端部に先住していた民族で、いまはおもに北海道に居住しています(二〇一三年の調査では道内に約一万七〇〇〇人が暮しています)。

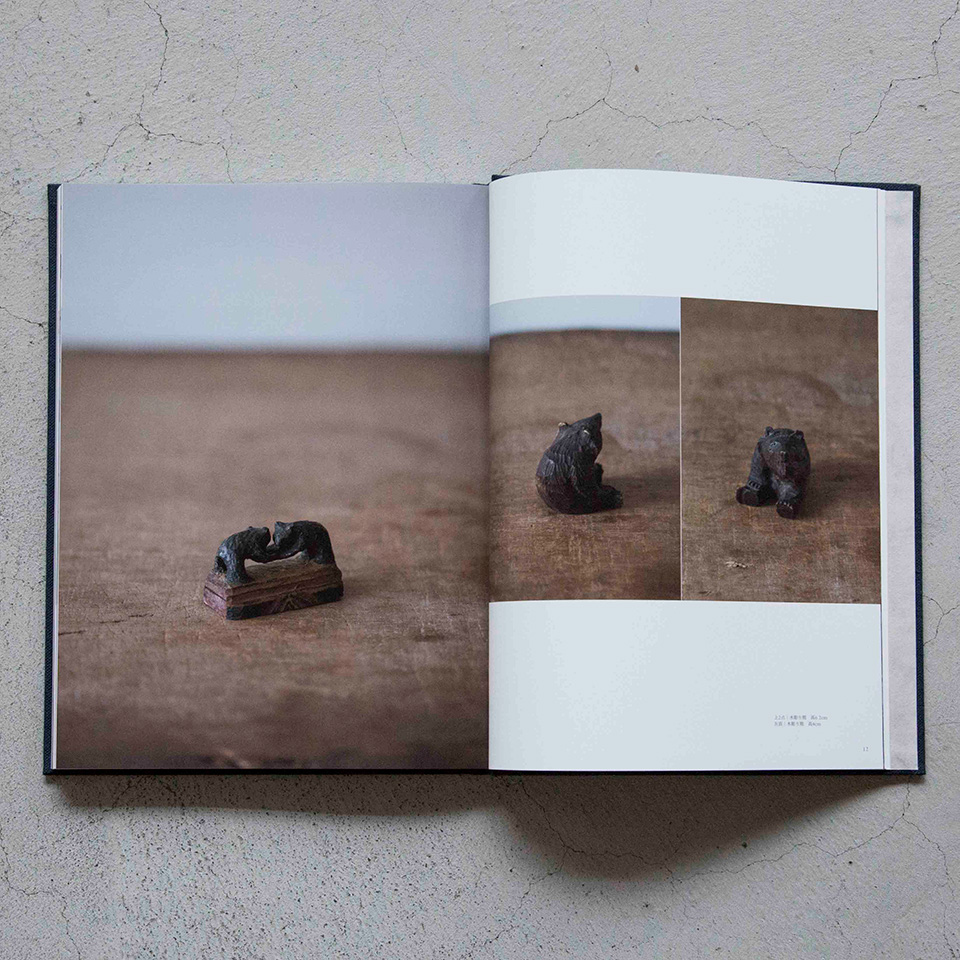

山岸由史子さん。札幌在住の刺繡作家で、アイヌ文様をモチーフにしています。以前は「クロノス」という工芸店もいとなんでいました。亡き夫は木工家の山岸憲史(一九二六—八九)で、やはりアイヌ工芸を範とした器やニポポ(土産物としてつくられた人形)で知られます。ふたりの作品を紹介します。

ショウヤ・グリッグさん。ニセコ在住のイギリス人写真家。一九九四年に来日、札幌でデザイン会社をおこし、のちニセコでホテル(坐忘林)やレストラン(SOMOZA)をはじめます。広大な自然と、とぎすまされた空間。その対比が劇的で、成功をおさめています。アイヌ工芸の収集家でもある彼の写真を掲載します。

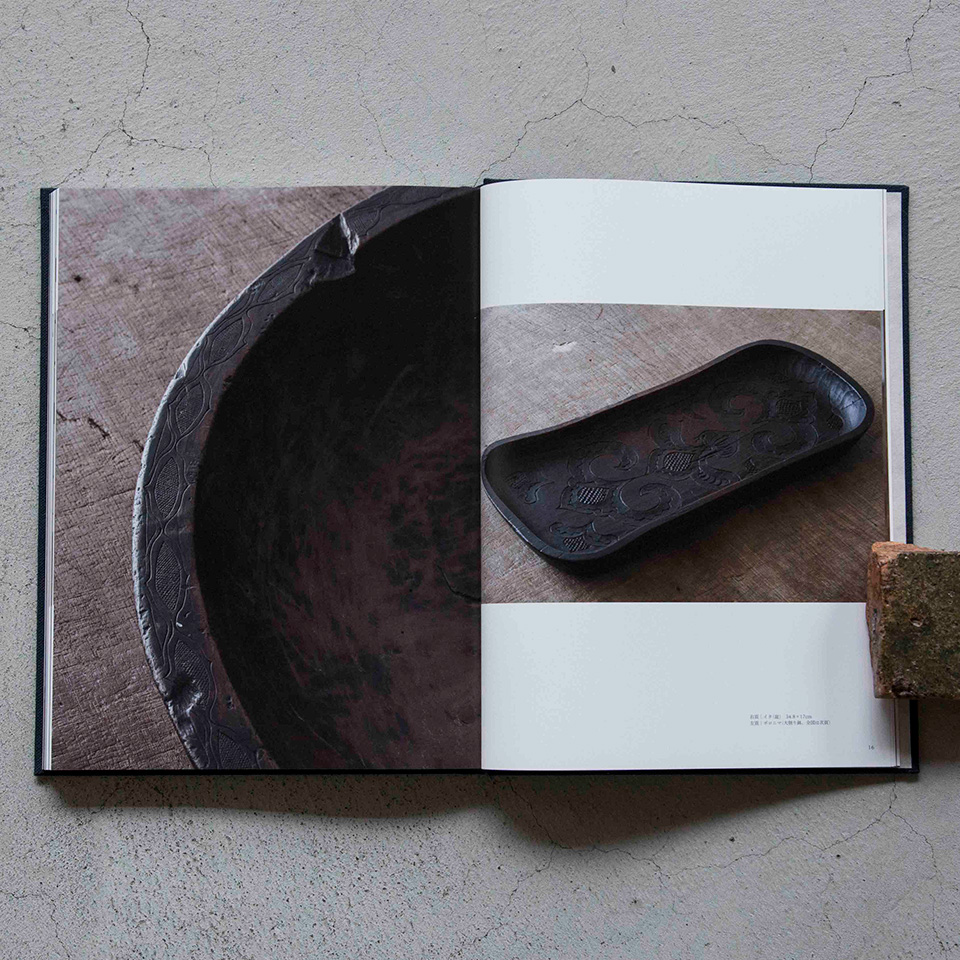

倉谷弥生さん。札幌在住。「古道具十一月」店主。二〇〇三年開業。倉谷さんの店には、たとえばブリキの雨戸や古紙の束、抽斗いっぱいの古釘などがあります。言葉にするとなんの変哲もないのですが、どれもたたずまいが独特で、ふつうの店ではありませんでした。アイヌの工芸品は近代に土産物としてつくられたものも多く(木彫り熊ほか)、アイヌ的なるものとはなにかは、なかなかむつかしい。今回はむしろ、倉谷的なるものをみせようと思いました。S

In Sapporo, there is a gallery called Sabita (Sabita is another name for Panicle hydrangea which bears white flowers in summer). A conversation with Mayumi Yoshida, the shop owner of Sabita inspired this collection of articles and photos introducing the work of the three artists.

The common theme among them is the Ainu (meaning a ‘man’ in their language). They are an indigenous people of Japan in Hokkaido, northern extremity of Honshu, Sakhalin, Kuril islands, and Kamchatka Peninsula, most of whom now live in Hokkaido (there were 17000 in Hokkaido according to a 2013 survey).

The first article is on Yoshiko Yamagishi, the embroidery artist, living in Sapporo. She takes her motifs from the traditional Ainu patterns. She used to own a craft shop called ‘Kronos’. Her late husband was the woodwork craftsman, Norifumi Yamagishi (1926─89) and was well-known for the wares based on the Ainu crafts and Nipopos (wooden dolls made as souvenirs). The article introduces the couple and their works.

The second article is on Shouya Grigg, the photographer, living in Niseko, Hokkaido. He came from Britain to Japan in 1994 and started a media design company in Sapporo. He now runs a hotel ‘Zaborin’ and a restaurant ‘Somoza’ at Niseko. The contrast of highly sophisticated architectural space in spectacular landscape is so dramatic making his business successful. The article introduces his photographs of his own collection of Ainu crafts.

The third article is on Yayoi Kuraya, who lives in Sapporo and has been the owner of antique shop 11gatsu (meaning ‘November’ in Japanese) since 2003. In her shop, there are things such as a tinplate shutter, a bunch of old paper, and a drawer full of old nails. By the description, it may not sound special, but the place has distinct atmosphere and is far from the ordinary. Many crafts of Ainu have their modern origins as souvenirs (the most well-known examples being wooden sculptures of a bear with a salmon), which makes it quite difficult for one to grasp the essence of Ainu. In this article, I have rather decided to introduce Kuraya’s uniqueness. (S)

2|生活工芸派と二〇一八年

New Standard Crafts Artists in 2018

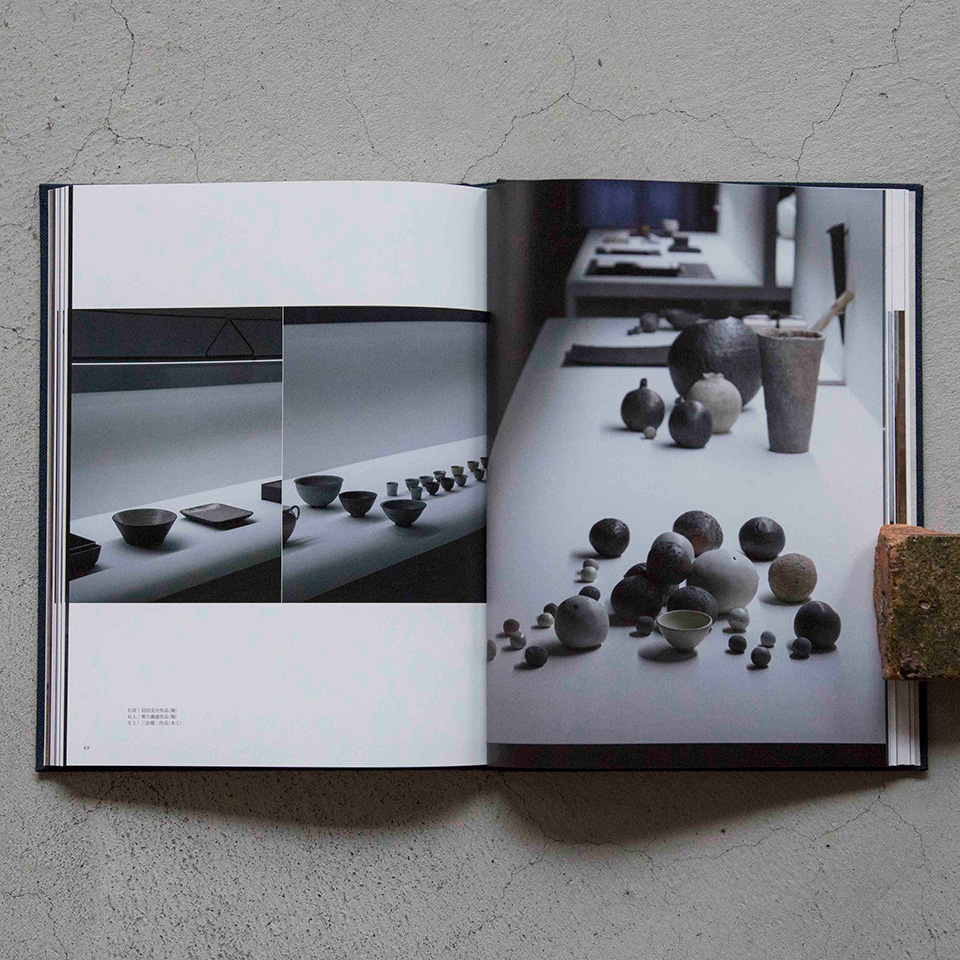

この特集は前後半にわかれています。前半は昨年(二〇一八年)一一月、台北でおこなわれた「日本生活器物展」について。企画者は木工家の三谷龍二さんと台湾の茶人謝小曼さんで、三谷さんほか計一三名の作家が参加しました。人選も三谷さんで、昨年刊行された三谷さんの本『すぐそばの工芸』の内容を立体化したような展示でした。本の主題が「生活工芸とはなにか」なので、台北の展観を「生活工芸展」としてみることもできます。文章は三谷さんのエッセイと、私(菅野)のレポート。会場構成を手がけた建築家の陳瑞憲さんと、台北展をみた建築家(で生活工芸派と親しい)中村好文さんにも話をききました。

「生活工芸派」とは、以下の五作家のことです。赤木明登(漆。一九六二年生れ)、安藤雅信(陶。一九五七年生れ)、内田鋼一(陶。一九六九年生れ)、辻和美(ガラス。一九六四年生れ)、三谷龍二(木工。一九五二年生れ)。なぜこの五人なのかは、特集後半の私の文章で説明しています。そこでも書きましたが、五人の作品から生活工芸的なるもの(概念)を抽出することが大事なのであって(様式的には無地/白、無国籍的といった特色があります)、生活工芸的な作家は五人以外にもいます。二〇〇〇年代は「生活工芸の時代」でした。

二〇一八年は『すぐそばの工芸』だけでなく、赤木さんの『二十一世紀民藝』、安藤さんの『どっちつかずのものつくり』と、生活工芸派三人の、それぞれ主著になりうるような本が刊行された年でした(二〇一〇年代にはじまる「生活工芸」の第一次歴史化のしめくくりの感がありました)。特集後半はその三冊評です。後続世代で、作家以外で、信頼できる書き手三人(工芸史家、カルチャー誌編集者、美術批評家)に依頼しました。S

This group of articles consist of two parts. The first part is on the exhibition ‘The Crafts for Everyday life in Japan’ in Taipei in November 2018. It was organized by Ryuji Mitani, the woodwork artist, and Xiaoman Hsieh, the expert in Taiwan-style tea ceremony. Thirteen artists participated, including Mitani, who also chose the other participating artists. The exhibition may be understood as something of an embodiment of ideas in Mitani’s book Living Crafts Beside Life published in 2018. Since the book’s theme is ‘What is New Standard Crafts?’, one can see the exhibition in Taipei as that of New Standard Crafts. The first part carries an essay by Mitani and my report on the exhibition. It also features two interviews: one with Ray Chen, the architect who designed the venue, and the other with another architect, Yoshifumi Nakamura, who went to the exhibition and personally knows these artists.

In my opinion, main artists of New Standard Crafts are the following five: Akito Akagi (the lacquerware artist, born in 1962), Masanobu Ando (the ceramic artist, born in 1957), Koichi Uchida (the ceramic artist, born in 1969), Kazumi Tsuji (the mouth-blown glass artist, born in 1964), and Ryuji Mitani (the woodwork artist, born in 1952). In the second part of the article I explain why I think these five are the main artists of New Standard Crafts. There are other artists in a similar vein. What is important is to extract the essence or concept of New Standard Crafts (stylistically their work is all white and plain, and stateless), for the 2000s in Japan was the age of New Standard Crafts.

2018 was a notable year when three out of above five New Standard Crafts artists published their books. Akagi’s Mingei in the Twenty-First Century was followed by Mitani’s Living Crafts Beside Life, and Ando’s Making Things One Way Or Another. All will be their literary magna opera. (2018 then seems to mark the year when the first historicising phase of New Standard Crafts concluded.) The second part is devoted to their reviews by authors in whom I place my confidence: an editor of culture magazine, an art critic, and a historian of crafts in Japan. All of them are from a younger generation and are not artists of crafts. (S)

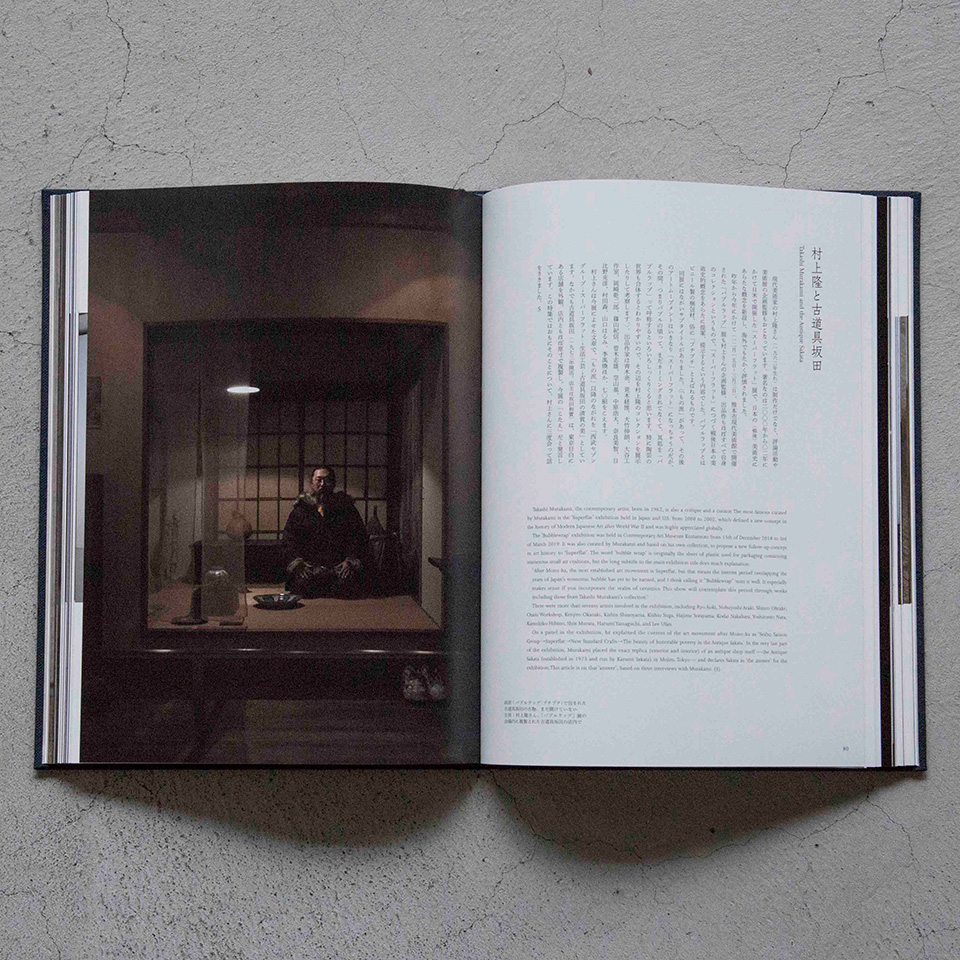

3|村上隆と古道具坂田

Takashi Murakami and the Antique Sakata

現代美術家の村上隆さん(一九六二年生れ)は制作だけでなく、評論活動や美術展の企画監修もおこなっています。著名なのは二〇〇〇年から〇二年にかけて日米で開催した「スーパーフラット」展で、日本の(戦後)美術史にあらたな概念を新設し、海外でもたかく評価されました。

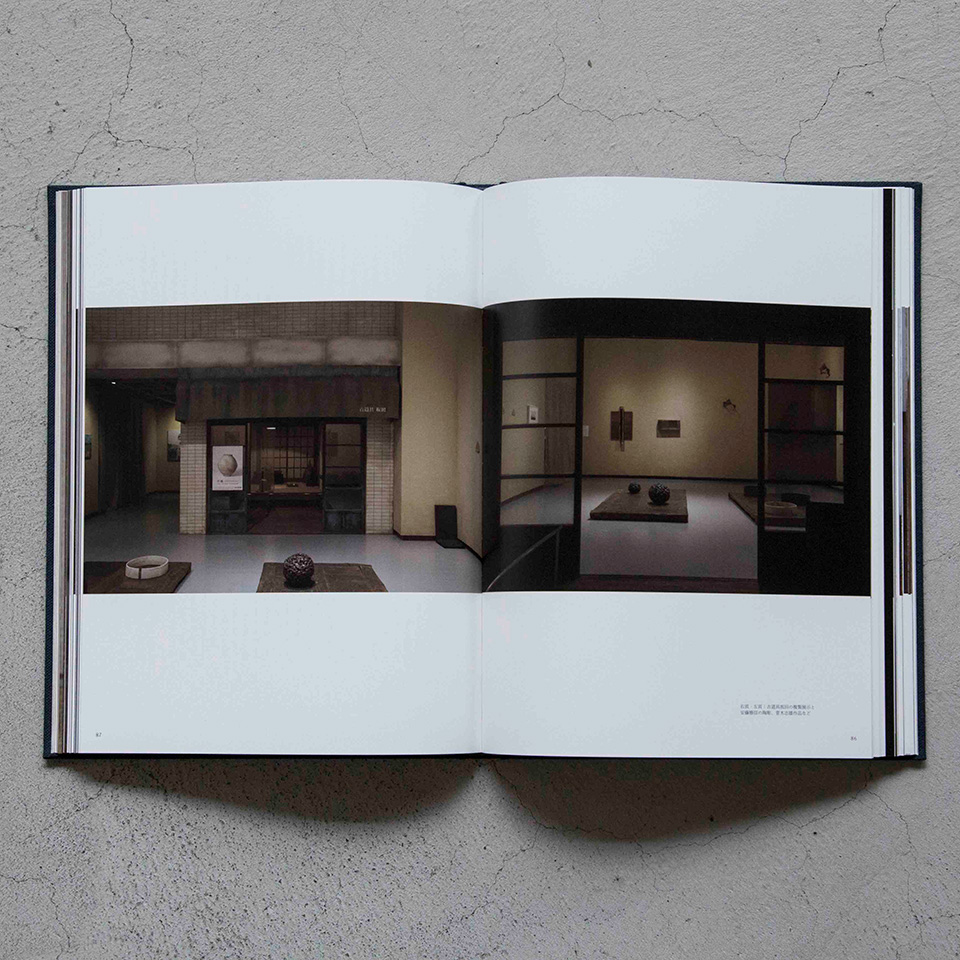

昨年から今年にかけて(一二月一五日—三月三日)、熊本市現代美術館で開催された「バブルラップ」展も村上さんの企画監修、出品作もほぼすべて自身のコレクションというもので、「スーパーフラット」につづく戦後日本の美術史的概念をあらたに提案、提示するという内容でした。バブルラップとはビニール製の梱包材、俗に「プチプチ」とよばれるものです。

同展にはながいサブタイトルがありました。〈「もの派」があって、その後のアートムーブメントはいきなり「スーパーフラット」になっちゃうのだが、その間、つまりバブルの頃って、まだネーミングされてなくて、其処を「バブルラップ」って呼称するといろいろしっくりくると思います。特に陶芸の世界も合体するとわかりやすいので、その辺を村上隆のコレクションを展示したりして考察します。〉。出品作家は青木亮、荒木経惟、大竹伸朗、大谷工作室、岡崎乾二郎、篠山紀信、菅木志雄、空山基、中原浩大、奈良美智、日比野克彦、村田森、山口はるみ、李禹煥ほか、七〇組をこえます。

村上さんは今展によせた文章で、「もの派」以降のながれを「西武セゾングループ→スーパーフラット→生活工芸→古道具坂田の清貧の美」としています。なかでも古道具坂田(一九七三年開店。店主は坂田和實)は、東京目白にある店舗を外観、店内ともほぼ原寸で複製し、今展の「こたえ」だと発言しています。この特集ではおもにそのことについて、村上さんに三度会って話をききました。S

Takashi Murakami, the contemporary artist, born in 1962, is also a critique and a curator. The most famous curated by Murakami is the ‘Superflat’ exhibition held in Japan and U.S. from 2000 to 2002, which defined a new concept in the history of Modern Japanese Art after World War II and was highly appreciated globally.

The ‘Bubblewrap’ exhibition was held in Contemporary Art Museum Kumamoto from 15th of December 2018 to 3rd of March 2019. It was also curated by Murakami and based on his own collection, to propose a new follow-up concept in art history to ‘Superflat’. The word ‘bubble wrap’ is originally the sheet of plastic used for packaging containing numerous small air cushions, but the long subtitle to the main exhibition title does much explanation:

‘After Mono-ha, the next established art movement is Superflat, but that means the interim period overlapping the years of Japan’s economic bubble has yet to be named, and I think calling it “Bubblewrap” suits it well. It especially makes sense if you incorporate the realm of ceramics. This show will contemplate this period through works including those from Takashi Murakami’s collection.’

There were more than seventy artists involved in the exhibition, including Ryo Aoki, Nobuyoshi Araki, Shinro Ohtake, Otani Workshop, Kenjiro Okazaki, Kishin Shinoyama, Kishio Suga, Hajime Sorayama, Kodai Nakahara, Yoshitomo Nara, Katsuhiko Hibino, Shin Murata, Harumi Yamaguchi, and Lee Ufan.

On a panel in the exhibition, he explained the current of the art movement after Mono-ha as ‘Seibu Saison Group→Superflat→New Standard Crafts→The beauty of honorable poverty in the Antique Sakata.’ In the very last part of the exhibition, Murakami placed the exact replica (exterior and interior) of an antique shop itself —the Antique Sakata (established in 1973 and run by Kazumi Sakata) in Mejiro, Tokyo— and declares Sakata as ‘the answer’ for the exhibition. This article is on that ‘answer’, based on three interviews with Murakami. (S)

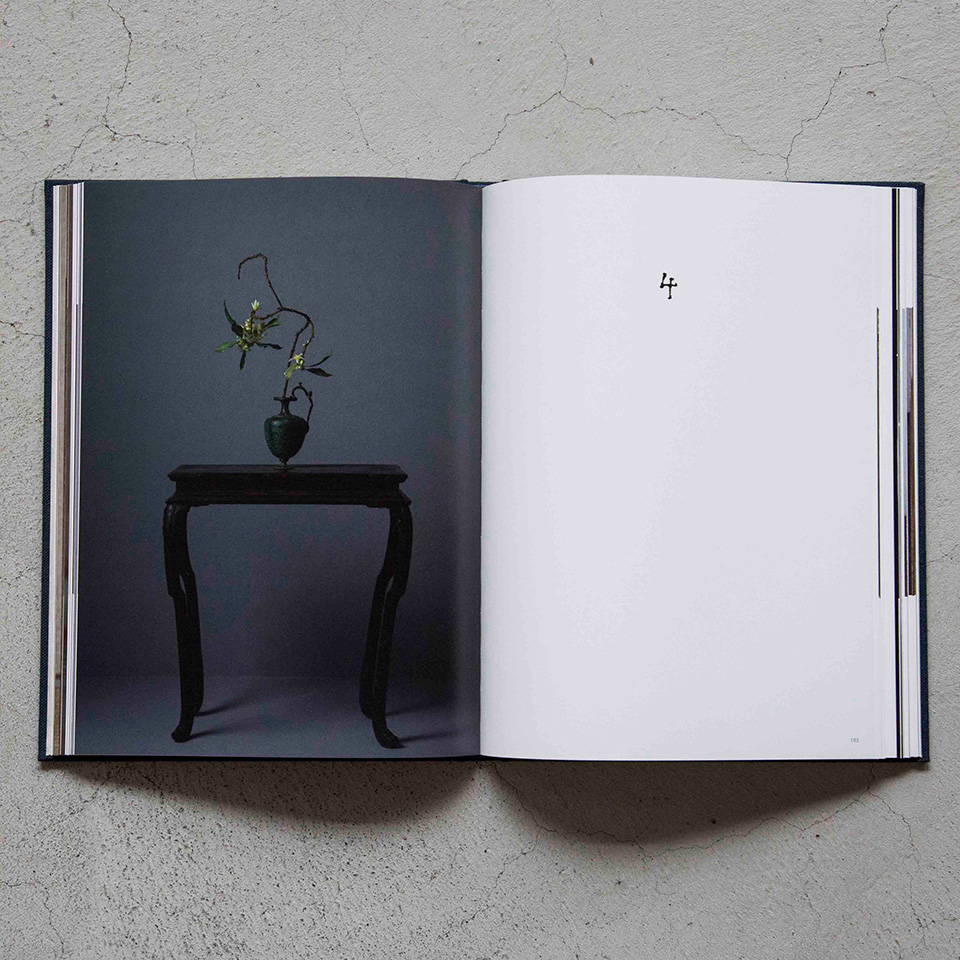

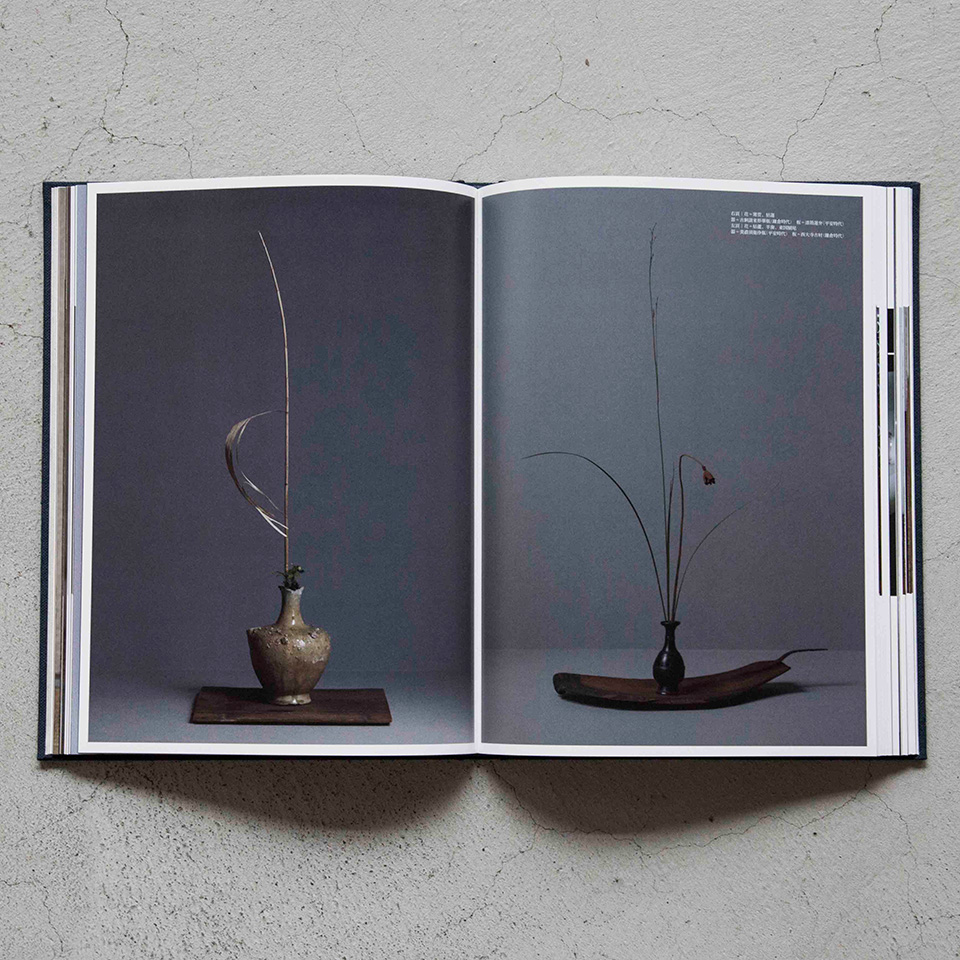

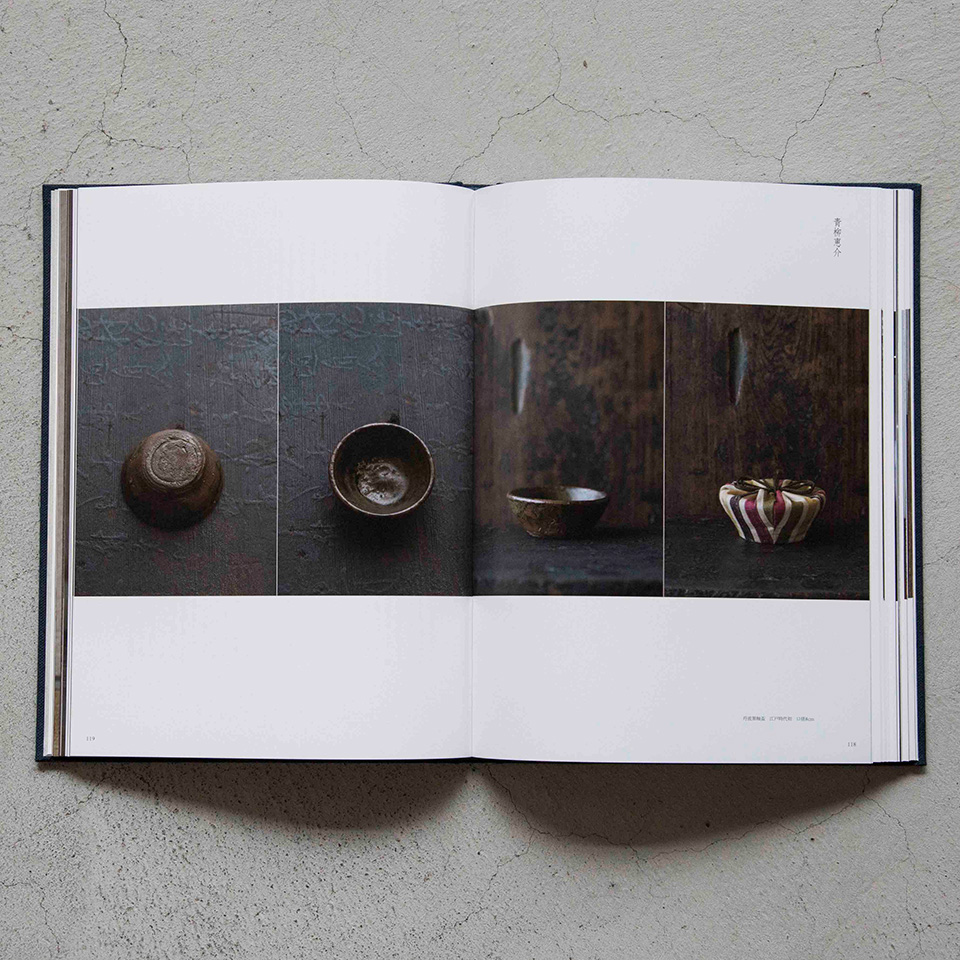

4|川瀬敏郎と甍堂

Toshiro Kawase at Irakado

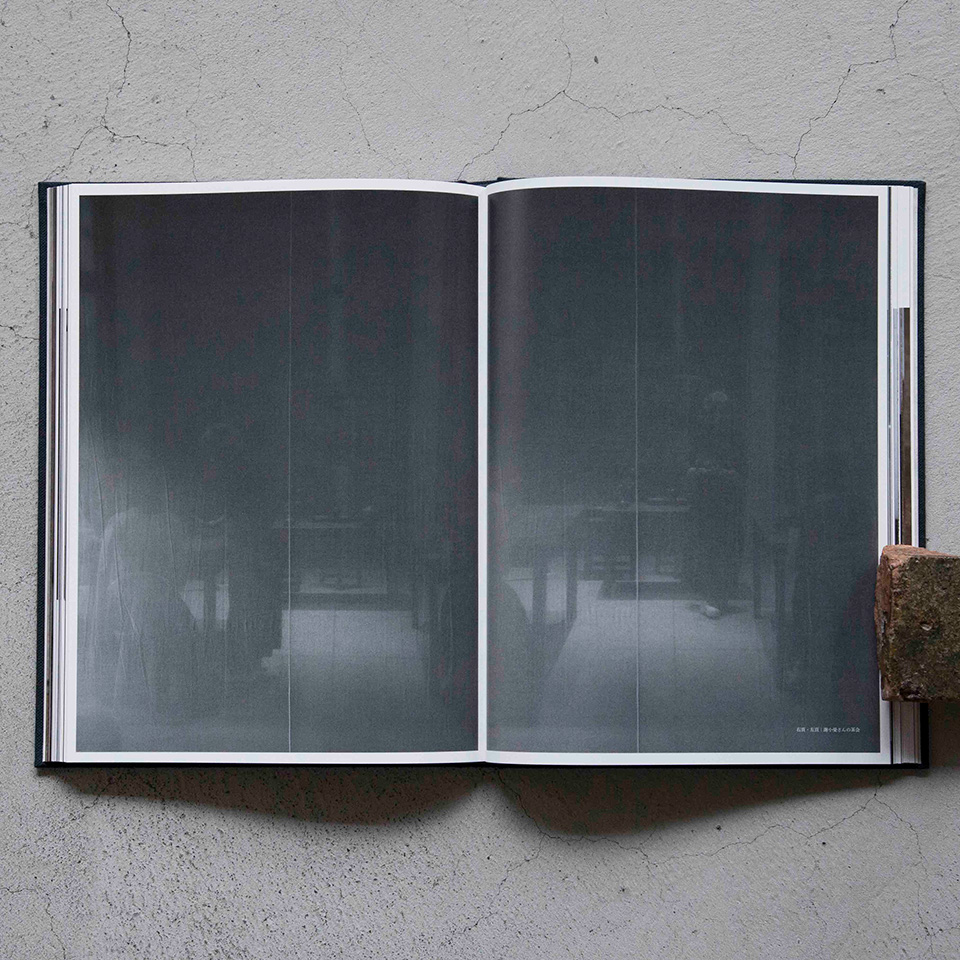

花人の川瀬敏郎さん(一九四八年生れ)の花、今回は古美術甍堂でいけています。器や花台、敷板なども甍堂のものです。甍堂主人の青井義夫さん(一九四九年生れ)と川瀬さんは旧知の間柄で、文章も青井さんにお願いしました。

現代の骨董界に青井さんがいてくれて、ほんとうによかったと思っています。国宝重文級の名品から残欠、雑器にいたるまで、眼(とふところ)の幅がひろく、しかもそこに「壁」をつくりません。骨董の現代的ありかたを、おそらく最良のかたちで体現しているひとりです。かつて青井さんと対談した古道具坂田の坂田和實さん(一九四五年生れ)はつぎのように語り、青井さんも首肯していました。〈僕が扱うものはボロボロだったり欠けていたり、甍堂にある名品とは比べものにならないのですが、それでも、どこか共通したところがあるようにも思うのです〉(『工芸青花』三号)

その対談で、青井さんはこう語っています。〈僕は平安時代の美術が好きで、日本美術を見るときの基準をあの時代に置いているところがあります。(略)あるとき、時代背景も重要だけれど、平安の美の理由はもっと根本的なこと、本居宣長のいう「もののあはれ」ではないかと思ったのです。宣長はそれを例えば「花の心を知ること」といっています。(略)実は平安のものは華奢ではありません。造形がしっかりしているからこそ、繊細にして強い線が出せるのだろうと思います〉

読みかえして、川瀬さんの花にたいする評のようだと思いました。S

In this issue, Ikebana artist Toshiro Kawase (born in 1948) arranged flowers in the antique shop Irakado. The flower vases, the vase rests, and the decking are all from the shop. The accompanying essay is written by Yoshio Aoi(born in 1949), the shop’s owner and a longtime friend of Kawase, who is a year older.

I deeply feel that we are lucky to have Aoi in the antique world in Japan. He deals masterpieces and their fragments, as well as miscellaneous wares. He has an acute eye (and a deep pocket) for a vast range of antique ware. He does not set a ‘wall’; everything is fairly judged before him. I consider him to be someone who has embodied many of the best aspects of the Japanese antique.

In his dialogue with Aoi recorded in Kogei Seika (Issue 3, 2015), Sakata Kazumi (the owner of the Antique Sakata, born in 1945) remarks: ‘The things I deal in are often those chipped and tattered, in no way comparable to masterpieces in Irakado. But I still see some kind of similarity in what each of us deals with.’ Aoi nods to that.

In the same dialogue, Aoi confesses, ‘I love the art from the Heian period. Perhaps, my standard for Japanese Art is that of the Heian period. […] While ago, I realized that the beauty of the Heian art lies not in its historical background, but in somewhere deeper, perhaps, in Mono-no-aware (feeling sadness or pathos of things) as Norinaga Motoori (the famous scholar of Japanese classical literature, 1730-1801) has defined as the key aesthetics of Japanese classical culture. Mono-no-aware, to Norinaga, is something like ‘to know the heart of a flower.’ […] The art of Heian is not fragile; it actually has an sturdiness in form, which brings about the line so delicate and bold.’

When I was re-reading this passage for this issue, I realized that this was exactly the words that described Ikebana by Kawase. (S)

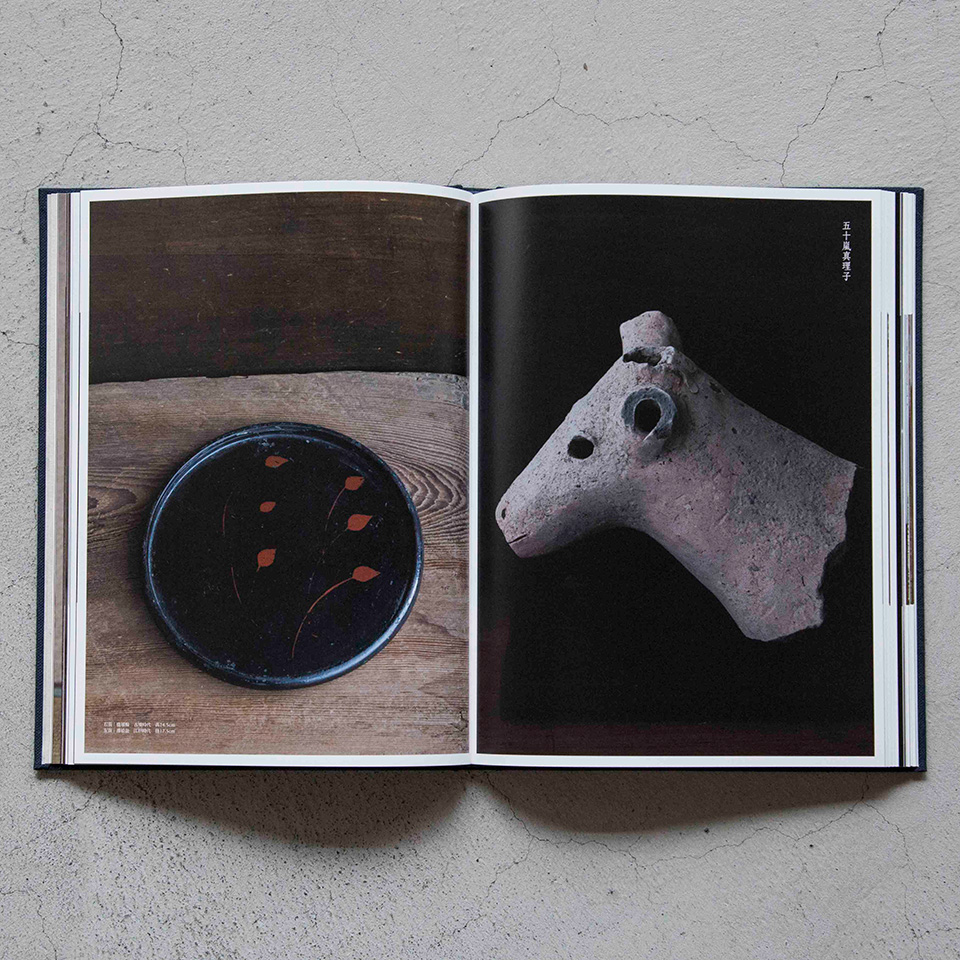

5|骨董のさびしさ

Loneliness in Antique

青花の会では毎年、各地の骨董商がつどう「骨董祭」を神楽坂でおこなっていて、当日小冊子も配布するのですが、今年はそのなかに、各出展者が好きな骨董本一冊をあげる、という記事がありました。複数の人があげていたのが『骨董屋という仕事 三五人の目利きたち』(一九九九年刊)。評論家、国文学者の青柳恵介さん(一九五〇年生れ)の著書です。私も座右の書です。

青柳さんの骨董歴は五〇年をこえるでしょう。青柳信雄(祖父。映画監督)、星野武雄(数寄者)、秦秀雄(骨董評論家)、白洲正子(随筆家)等々、戦後の骨董史に名をのこす人々との交歓をこれまできいてきました。前掲書も史記列伝のように読めます。

〈人生の終盤にさしかかり、若いころからの手許不如意の度は進むばかり、さらに視力も衰えてくると骨董に対する欲望も減退してくる道理である〉

今回、青柳さんによせていただいた文章の冒頭です。欲望が減退したいまの青柳さんの骨董観を知りたいと思いました。

「骨董祭」のロゴは手書き文字で、草友舎の五十嵐真理子さん(骨董商)にお願いしたものです。筆跡だけでなく、店内にいけられた花にも、おいてある古物にもあきらかな五十嵐さんらしさがあり、それにひかれてきました。掲載した品々は「さびしさ」というテーマをつたえてえらんでいただいたものです。ひそけさ、でもよかったかもしれません。S

Every year, we host the Antique Festival to which antique dealers come together from all over Japan. During the festival, we give out pamphlets. This year’s issue contains an article in which every participating dealer introduces one of his or her favourite book on antique. Many mention a 1999 book, titled Antique Dealers in Japan: Thirty-Five Connoisseurs by Keisuke Aoyagi, a critique and scholar of Japanese literature, born in 1950. The book is my favourite, too.

His career as an antique lover comfortably exceeds fifty years. He has associated with many whose names are engraved in the history of Japanese antique, including his grandfather Nobuo Aoyagi (a film director), Takeo Hoshino (a man of refined tastes), Hideo Hata (an antiques critic), and Masako Shirasu (an essayist), to name but only a few. His book can be read like the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian of ancient China, only dealing with the modern Japanese antique history.

‘In the endgame of my life, I am even worse off than when I was young, and with quailing eyesight, it is natural that my appetite for antique is declining.’ This is the first sentence of Aoyagi’s essay for this issue. I wanted to know his current views on antique, with his desire for antique weakening.

The logo for the Antique Festival is created by Mariko Igarashi (the antique dealer in Soyusha) in her hand writing. I have always been attracted to her calligraphy, her flower arrangements, and antique objects in her shop, each so unique. The objects photographed here are selected by her, according to a theme I requested: ‘Loneliness’. Perhaps, it could have been ‘Quietness’. (S)