『工芸青花』13号

■2020年1月30日刊

■A4判|麻布張り上製本|見返し和紙(楮紙)

■カラー120頁|望月通陽の型染絵を貼付したページあり

■限定1100部|10,000円+税

■御購入はこちらから

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=319

Kogei Seika vol.13

■Published in 2020 by Shinchosha, Tokyo

■A4 in size, linen cloth coverd book with endpaper made of Japanese paper (kozo)

■120 Colour Plates, Frontispiece with a stencil dyed art work by Michiaki Mochizuki

■Each chapter is accompanied by an English summary and all photographs are with captions in English

■Limited edition of 1100

■10,000 yen (excluding tax)

■To purchase please click

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=319

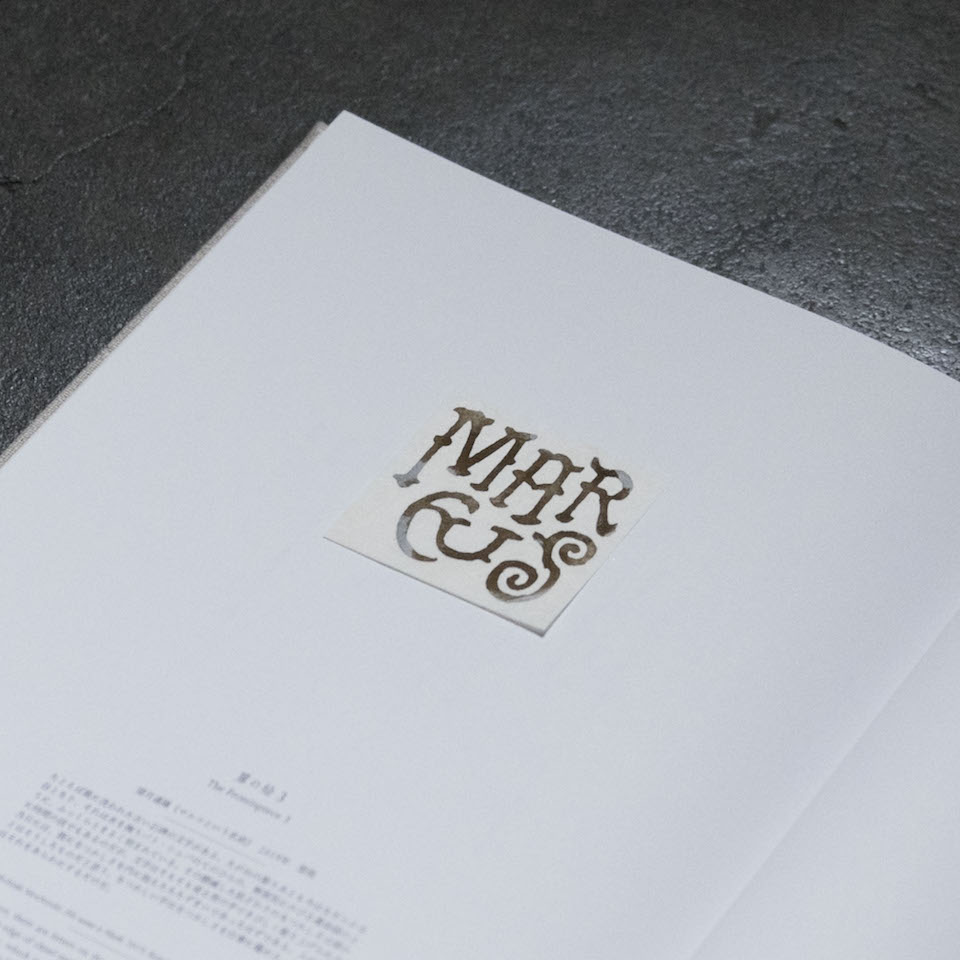

扉の絵 3

The Frontispiece 3

望月通陽《マルコという名前》 2019年 型染

たとえば風に洗われた古い石碑の文字がある。たがねの彫りあとも今はなだらかな谷となり、それは水を掬うバト・シェバのてのひらの、無邪気にのびる運命線のように、ふっくらとまるく刻まれている。その磨滅した肌ざわりのなつかしさは確かに時間の技でもあるのだが、文字はそもそも或る男の手できびしく彫り上げられた当日には、既になつかしさを内に抱えたたたずまいであったはずである。人の仕事とはそうしたものだと思う。なつかしい手はなつかしさを仕事に籠める。風と時間はそれをあらわにするだけだ。(望月通陽/染色家)

Michiaki Mochizuki, His name is Mark, 2019, Katazome (Japanese stencil print)

For instance, there are letters on the ancient stone monuments, weathered by wind. The sharp edge of chisel marks has been smoothed and now it is like a valley with gentle slopes, which is round and plump like the line of Fate of Bathsheba’s hand, scooping water for bathing. The nostalgic feeling towards the abrasion of the touch is certainly due to the lapse of time. However, the letters bear such nostalgy innately, on the day they are engraved rigorously by a man. I believe that one’s vocation should be such. The nostalgic hand can insert nostalgy into his work. The wind and the time are doing nothing but revealing it. (Michiaki Mochizuki / Artist)

目次 Contents

1 スイスのロマネスク ミュスタイアのザンクト・ヨハン修道院

Romanesque Art in Switzerland, Kloster St. Johann in Mustair

・尼僧院の椅子 金沢百枝

・カール大帝の修道院 小澤実

2 川瀬敏郎の花 杉本家住宅

Flowers by Toshiro Kawase at Sugimoto Residence in Kyoto

・花に偲ぶ文人―父・杉本秀太郎 杉本歌子

3 民藝と美

The Beauty in Mingei

・柳宗悦の「直観」 月森俊文

・脳にとって美とはなにか 前橋重二

連載 Series

・ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群7 堀江敏幸

扉の絵

精華抄

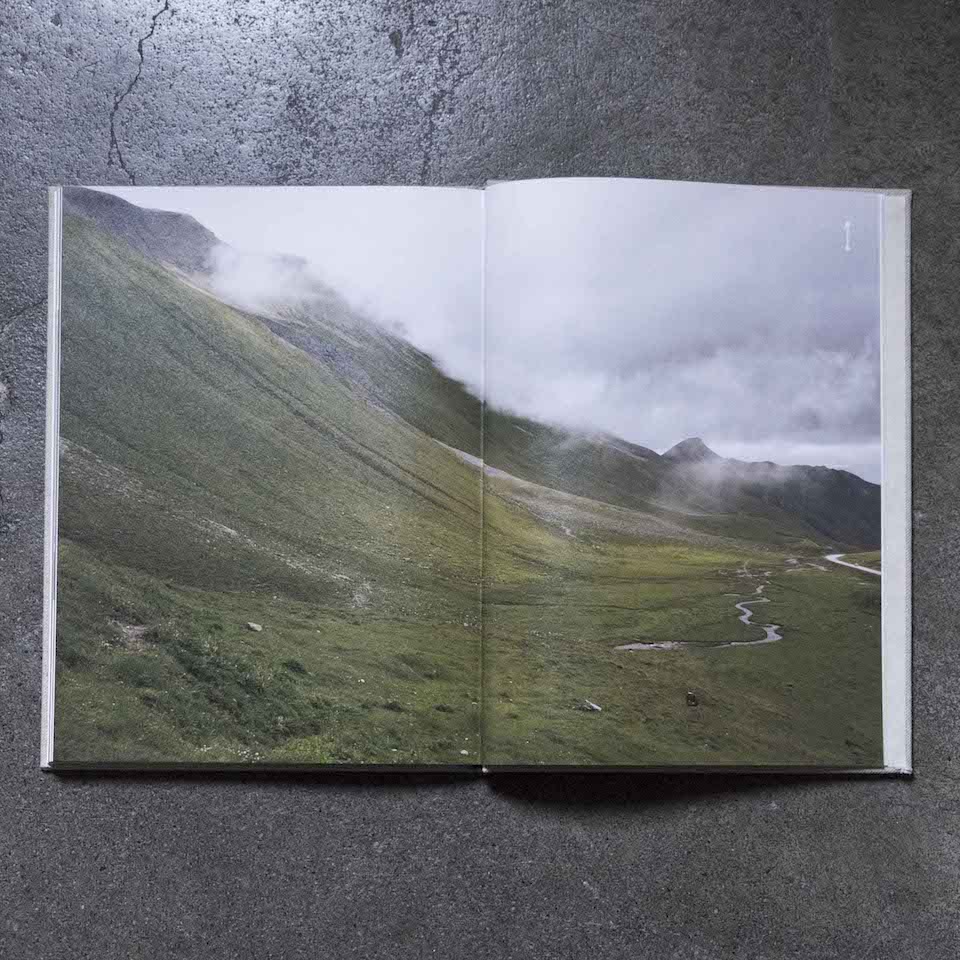

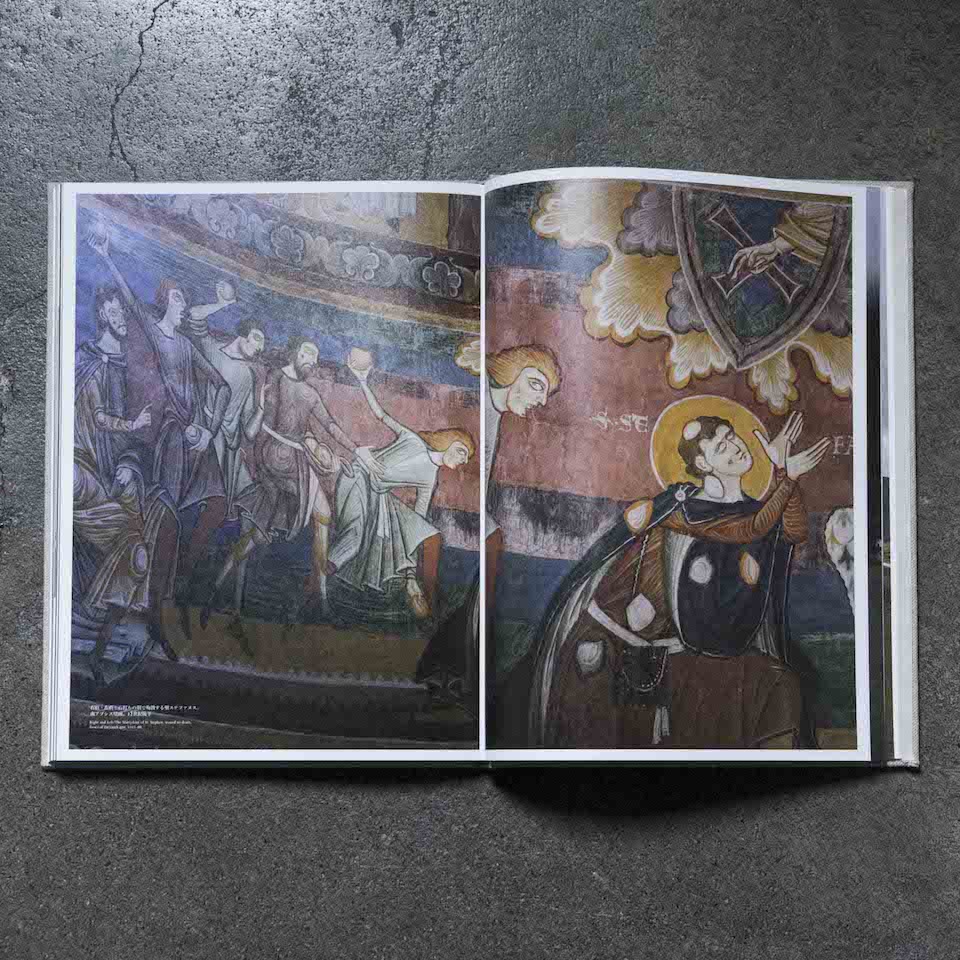

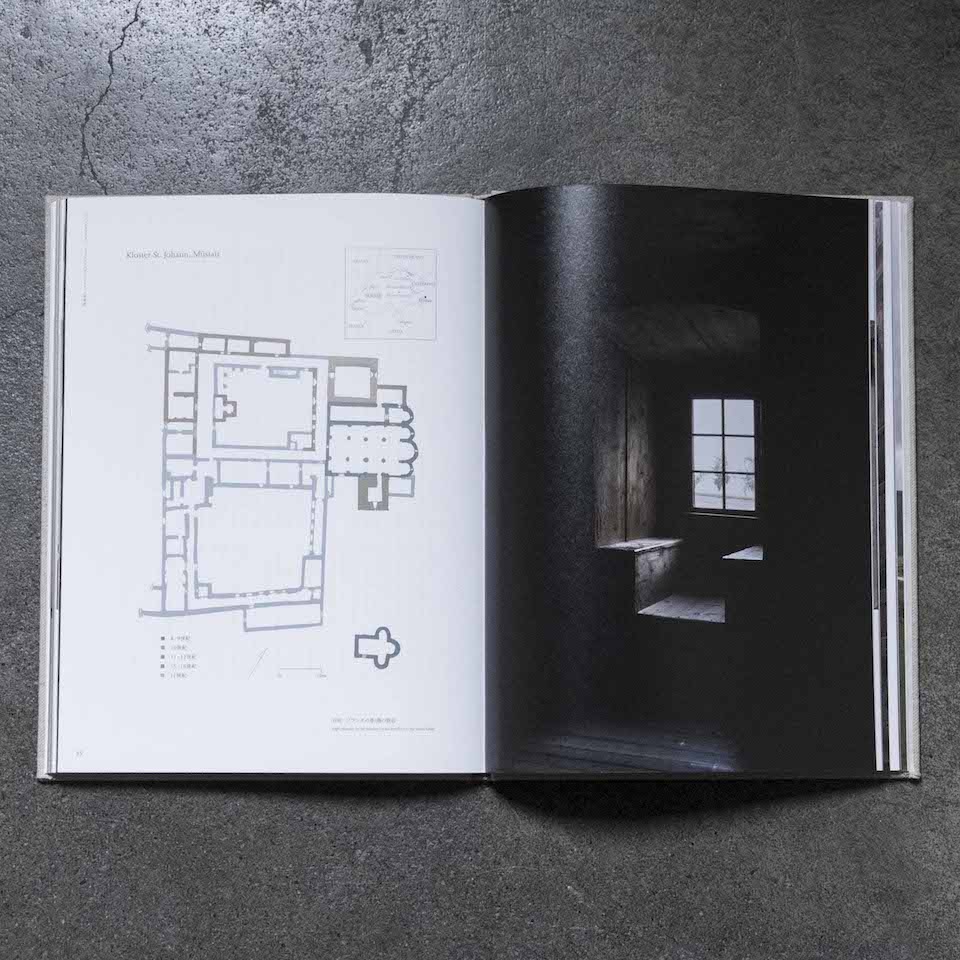

1|スイスのロマネスク ミュスタイアのザンクト・ヨハン修道院

Romanesque Art in Switzerland, Kloster St. Johann in Mustair

西洋中世のロマネスク美術(一一—一二世紀)を紹介する記事です。前回(一〇号)につづいてスイス、今回はミュスタイアのザンクト・ヨハン修道院をたずねました。ベネディクト会の女子修道院で、いまも修道女たちが暮しています。ミュスタイアはスイスの東端、イタリアとの国境ぞいの山間の地です。

創建は七七五年ごろ、カール大帝治下のフランク王国領で、美術史的にはカロリング朝美術の時代です。聖堂の建築と壁画は改築、傷みはあるものの、カロリング美術の稀少な遺例として知られています。

カロリング期の壁画は堂内全体に描かれましたが、一二世紀末、東側の三つのアプシス(祭室/後陣)にあらたに「聖ステファヌス」「洗礼者ヨハネ」「聖アンデレ」を主題とする壁画が描かれました。それが今回の本題であるロマネスク美術です。

先日とどいた雑誌『民藝』二〇一九年一二月号の特集は「中世紀基督教藝術と柳宗玄」でした。本特集の筆者金沢百枝さんも寄稿していて、柳宗悦(一八八九—一九六一)のロマネスク評価(一九三〇年代)が世界的にもさきがけだったと述べています。

以下は同誌に再録された柳宗悦の文章から。〈恐らくグロテスクの美を捕え得るか否かで方向が決まる。近時日本ではこの大切な言葉が、卑俗極まる意味に陥って了った〉〈併し本来の意義はそんなものではない。グロテスクの要素なくして、どんな偉大な宗教芸術もあり得ない〉〈自然がかく煮つめられてその表現が濃くなる時、ここにグロテスクの美が生れる〉〈それは充実された力の現れである。「渋さの美」と人々が呼んだものは、畢竟グロテスクの美である〉(「信と美との一致に就て」)

たとえば李朝中期の白磁とロマネスク美術をともに(似ていないのに)「渋い」と感じる理由は、こうしたことなのかもしれません。S

The series introduce the Romanesque art (11th to 12th century) in Europe. Since issue no.10, we have moved on to Switzerland. The article in this issue is on the Convent of St. John the Baptist in M?stair, situated in the most eastern valley of Switzerland, just 1km away from Italy. In the Benedictine convent, the nuns continue to live their pious life as in the Middle Ages.

The foundation of the monastery is around 775, when the area was ruled by Charlemagne, the Emperor of the Frankish Empire. Although there are some renovation and damage, it is known as the amazingly intact Carolingian church.

The entire wall of the church was decorated by Carolingian fresco. When the monastery was handed over to the nuns in twelfth century, the three apses were repainted in Romanesque style. In the apses, we can see the martyrdom of three saints; St. Stephen in the south, St. John the Baptist at the centre, and St. Andrew in the north. The article is mainly on these Romanesque frescoes.

The latest issue of Mingei (December 2019) features ‘the Christian Art in the Middle Ages and Munemoto Yanagi’. Momo Kanazawa, one of the writers of this article, also contributed in the issue. According to Kanazawa, the founder of Mingei movement, Soetsu Yanagi (1889-1961) appreciated highly of Romanesque art already in 1930s. Making him one of the earliest admirers of Romanesque art in the modern era.

The following passage is of Soetsu Yanagi, cited in the article.

‘Perhaps the critical point is the appreciation of the beauty of grotesque. Now a days in Japan, this important word has attained the most vulgar nuance.’ ‘It is far from its original meaning. I believe that without the grotesque element, no religious art can be glorious.’ ‘When nature is reduced down to the deepest of the expression, the beauty of the grotesque emerges.’ From S. Yanagi, Integrity of the Faith and the Beauty, 1942.

This essence of grotesque may be the answer to why I find the white porcelain of Joseon dynasty and the Romanesque art, tasteful, though they are from a totally different background. (S)

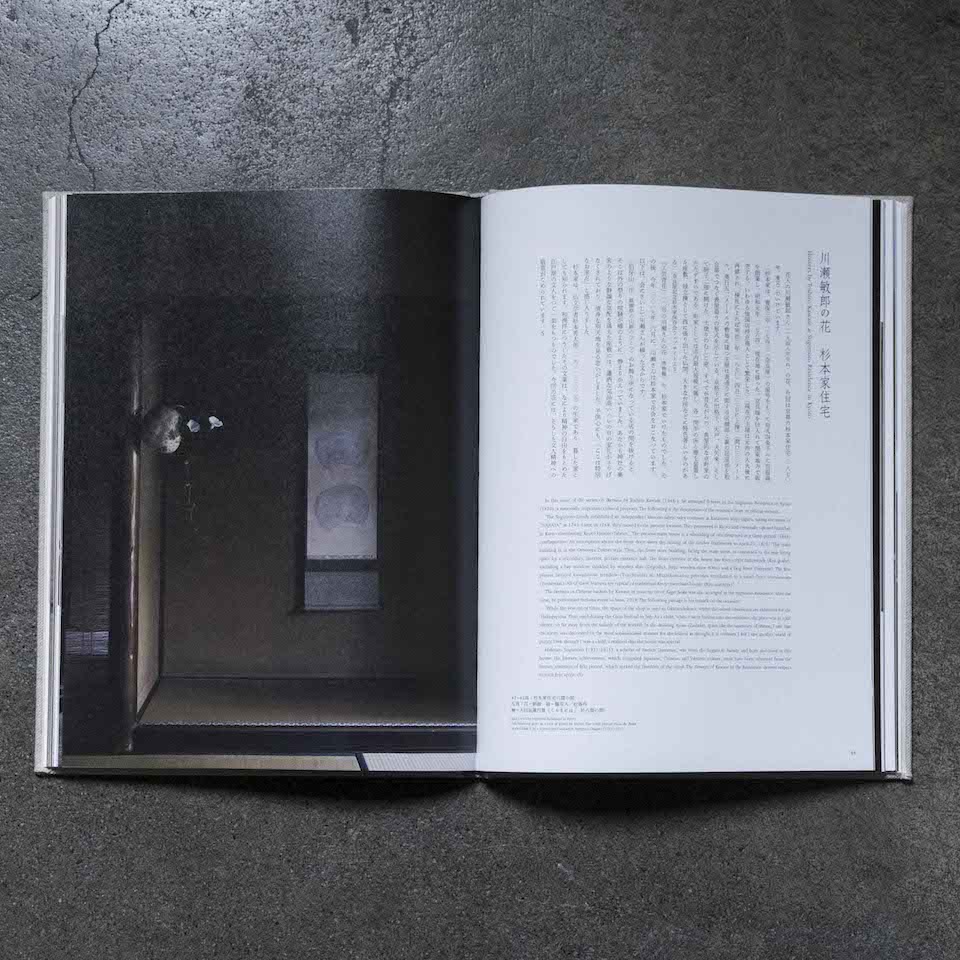

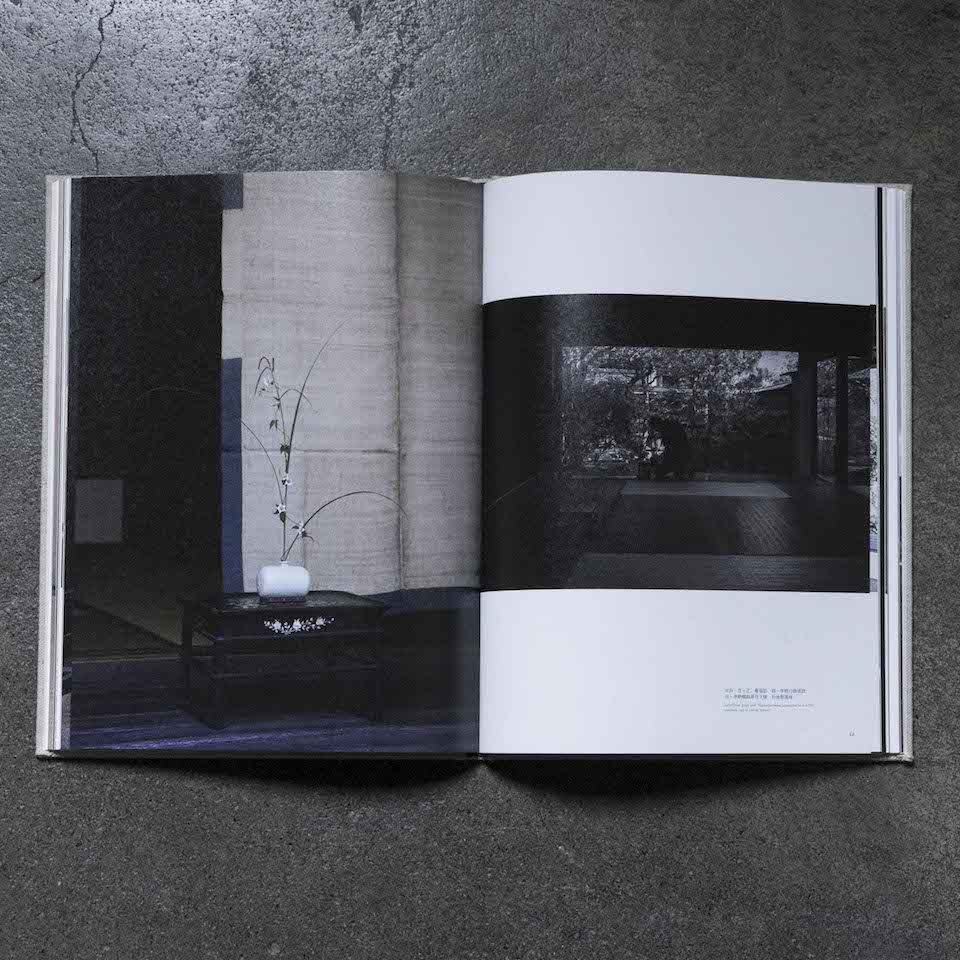

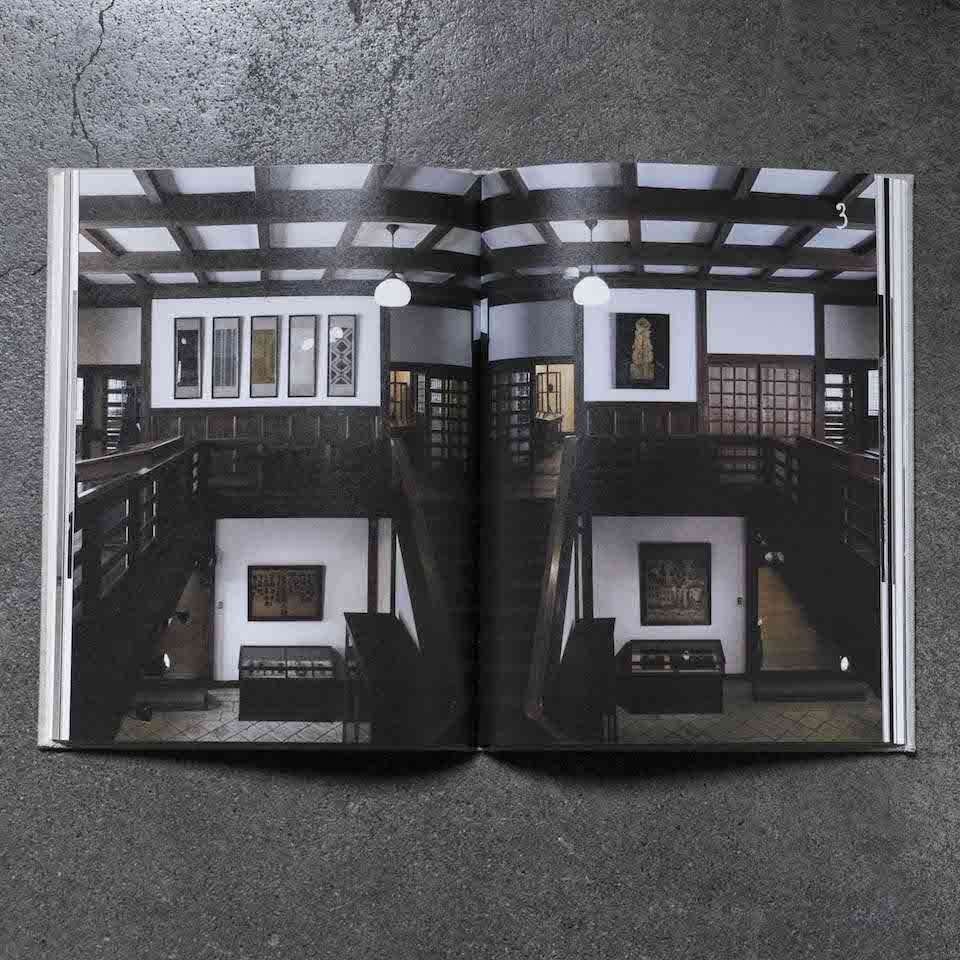

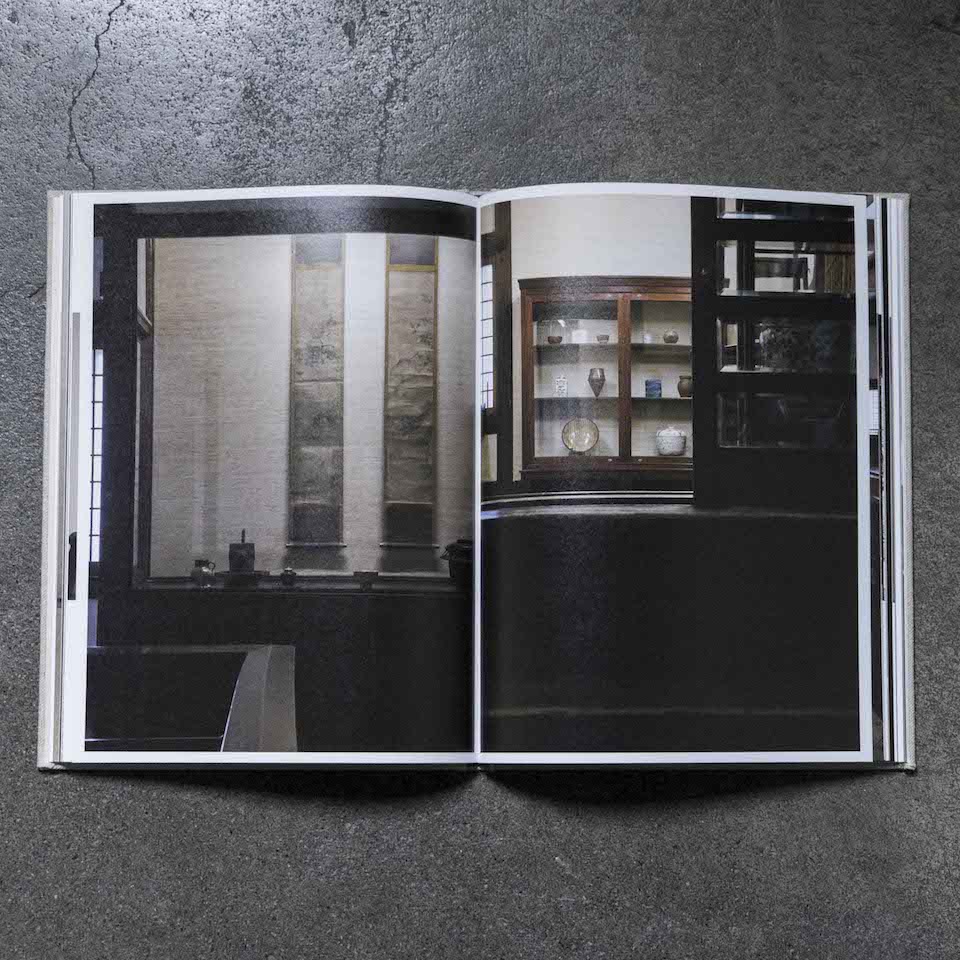

2|川瀬敏郎の花 杉本家住宅

Flowers by Toshiro Kawase at Sugimoto Residence in Kyoto

花人の川瀬敏郎さん(一九四八年生れ)の花、今回は京都の杉本家住宅(一八七〇年。重文)でいけています。

〈杉本家は、寛保三年(一七四三)「奈良屋」の屋号をもって烏丸四条下ルに呉服商を創業し、明和元年(一七六四)、現在地に移った。京呉服を仕入れて関東地方で販売する、いわゆる他国店持京商人として繁栄した〉〈現在の主屋は元治の大火後に再建され、棟札によれば明治三年(一八七〇)四月二三日に上棟〉〈間口三〇メートル、奥行五二メートルの敷地に建つ主屋は表通りに面する店舗部と裏の居室部を取合部でつなぐ表屋造りの形式を示している。京格子に出格子、大戸、犬矢来、そして厨子二階に開けた、土塗りのむしこ窓。すべてが昔ながらの、典型的な京町家のたたずまいである。町家としては市内最大規模に属し、各一間半の床と棚を装置した座敷、独立棟として西に張り出した仏間、大きな台所などに特色著しいものがある〉(奈良屋記念杉本家保存会ウェブサイトより)

『工芸青花』一〇号の川瀬さんの花(唐物籠)も、杉本家でいけたものでした。その後、今年(二〇一九年)六月に、川瀬さんは杉本家で花会をおこなっています。以下は、会にさいして川瀬さんが綴った文からです。

〈伯牙山(注・祇園祭の山鉾のひとつ)のお飾り所になっている店の間を抜けると、そこは外の祭りの喧騒が嘘のように、静まりかえっていました。あたかも神社の奥宮のような静謐な気配を湛えた座敷には、瀟洒な気品高いハレの日の室礼がさりげなくされており、清浄な別天地を見る思いがしました。子供心にも、「ここは特別なお家だ」と感じ入りました〉

杉本家は、仏文学者杉本秀太郎(一九三一—二〇一五)の生家であり、暮した家としても知られます。和漢洋につうじたその文業は、なにより精神の自由をもとめた江戸期の文人をつぐ一面をもつものでした。今回の花には、そうした文人精神への敬意がこめられています。S

In this issue of the series on Ikebana by Toshiro Kawase (1948-), he arranged flowers in the Sugimoto Residence in Kyoto (1870), a nationally important cultural property. The following is the description of the residence from its official website.

‘The Sugimoto family established an independent kimono fabric sales company at Karasuma Shijo sagaru, taking the name of “NARAYA” in 1743. Later, in 1764, they moved to the present location. They prospered in Kyoto and eventually opened branches in Kanto distributing Kyoto kimono fabrics.’ ‘The present main house is a rebuilding of one destroyed in a Genji period (1864) conflagration. An inscription above the front door dates the raising of the timber framework to April 23, 1870.’ ‘The main building is in the Omoteya-Zukuri style. Thus, the front store building, facing the main street, is connected to the rear living space by a secondary, interior, private entrance hall. The front exterior of the house has Kyoto-style latticework (Kyo-goshi), including a bay window shielded by wooden slats (Degoshi), large wooden door (Odo) and a Dog fence (Inuyarai). The fine plaster latticed townhouse window (Tsuchinuiri no Mushikomado) provides ventilation to a small floor storehouses (Zushinikai). All of these features are typical of traditional Kyoto merchant houses (Kyo-machiya).’

The Ikebana in Chinese baskets by Kawase in issue no.10 of Kogei Seika was also arranged in the Sugimoto Residence. After the issue, he performed Ikebana event in June, 2019. The following passage is his remark on the occasion.

‘While the Festival of Gion, the space of the shop is used as Okazaridokoro, where the sacred ornaments are exhibited for the ‘Hakugayama’ float used during the Gion Festival in July. As a child, when I went further into the residence, the place was in total silence, so far away from the tumult of the festival. In the drawing room (Zashiki), quiet like the sanctuary of Shrine, I saw that the room was decorated in the most sophisticated manner for the festival as thought it is ordinary. I felt I saw another world of purity. Even though I was a child, I realized that the house was special.’

Hidetaro Sugimoto (1931-2015), a scholar of French Literature, was from the Sugimoto Family and born and lived in this house. His literary achievement, which compiled Japanese, Chinese, and Western culture, must have been inherited from the literary tradition of Edo period, which seeked the freedom of the mind. The flowers of Kawase in the Residence showed respect to such free spirit. (S)

3|民藝と美

The Beauty in Mingei

二〇一九年の一月から三月にかけて、東京の日本民藝館でひらかれた「柳宗悦の『直観』─美を見いだす力」展には、日本、東洋、欧米、南米、アフリカもの、紀元前から二〇世紀のものまで、館蔵品二八一作がならびました。宗悦、宗理親子以外の収集品もありました。えらんだのは同展担当の月森俊文さんです。名品展と称してもよいような内容でありつつ、これまで展示されたことのないような、それでいてみどころあるもの(たとえば新館広間の飼葉桶など)もでていました。

展示もみごとでした。名品ぞろいということは、個性派ぞろいということです。それを時代順でも分野別でもなく、色、かたち、質感等のとりあわせでみせていました。

そして、なによりおどろいたのは、個々の作についての文字情報が(事前も事後も)いっさいなかったことです。〈品名も解説もいっさいなし(最後までない)の展示が話題ですが、私のまわりでも、来場者にも好評とのこと。批判、罵倒も覚悟のうえでひとりで企画、実現した民藝館の月森さんの心意気に感じいる。「解説デトックス」が思いのほかとてもすがすがしい(民藝館のキャプションはふだんからひかえめですが、それでも、文字の残像のつよさを思い知る)〉(初見時に記した青花のブログより)

月森さんは書きます。〈造語された民藝という言葉は(略)多くの誤解を受け、そして現在も受けつづけていると思います。大きな誤解のひとつは民衆的工藝、つまり民衆が使っていた日用品はおしなべて民藝だと断定されてしまうことでしょう。そこには「美しいもの」であるという、最も大切な特質が抜け落ちているのです。(略)ではどのようにすればものの美しさを見届けられるかといえば、それにはどうしても直観が必要であると、柳は繰り返し説きます〉。柳は、直観をさまたげるものは知識(先入観)/言葉(概念)だといいます。それはあとでいい、と。S

The exhibition ‘Direct Perception by Soetsu Yanagi’ was held at The Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo, from January to March, 2019. Two hundred and eighty one objects from the Collection, ancient and modern, were from various part of the World. There were objects other than the collections of Soetsu and Sori (the founder of the Museum and his son). The objects were selected by the curator, Toshifumi Tsukimori. Most of them were the masterpiece of the Museum, but some were those which has never been on the show, despite their quality, such as a manger exhibited in the hall of the new building.

The way he displayed was also splendid. The unique masterpiece was side by side by things of different origins. He arranged the objects not in timeline, nor by medium types but arranged in accordance with their colour, form and the texture.

The most amazing thing in the exhibition was that there were no captions. No data for objects was provided for the visitors, neither before, nor after the exhibition. I have written the impression of the exhibition on the website of Seika, as follows.

‘The exhibition without any title or legend is much discussed. My friend talked about it favourably and I heard that it is also popular to the visitors. I admire the courage of Tsukimori who planned and realized the exhibition on his own, prepared for critisim and bashing. ‘Caption detox’ feels more refereshing than I had expected. Even though captions in The Japan Folk Crafts Museum are always moderate, I came to know that the afterimage of letters are amazingly strong.’

Tshukimori writes, ‘The coined word Mingei (…) has been and is being misunderstood. One of the biggest misunderstanding is that it is the craft (工藝) for the common people (民), the notion to define all the everyday ware in popular use to be Mingei. In such notion, the essential point that Mingei should be beautiful is missing. (…) Yanagi repeatedly writes that to verify the beauty, by all means, the direct perception is necessary.’ ‘The disturbance of the direct perception is the knowledge (preconception) /language (concept). You can have those after you see them, also says Yanagi. (S)